John Mearsheimer is one of the most cited and simultaneously controversial political scientists of our time. His views on the causes of the war in Ukraine provoke sharp criticism: opponents accuse the professor of essentially broadcasting Russian narratives, placing responsibility for the conflict on NATO expansion rather than Kremlin aggression. Mearsheimer himself insists he merely analyzes reality through the lens of structural realism—a theory that explains state behavior through the logic of power, not morality. In conversation with former Serbian Foreign Minister Vuk Jeremić, he calls the war "a complete catastrophe" for Ukraine, argues that Biden "acted irrationally," claims Trump is trying to "correct a strategic mistake," and warns: even after a ceasefire, Europe will remain a powder keg with seven potential flashpoints.

Vuk Jeremić: It's a rare privilege to introduce a scholar whose ideas have not only shaped academic debate but fundamentally influenced how policymakers, journalists, and citizens around the world understand power, conflict, and the tragic dynamics of international politics.

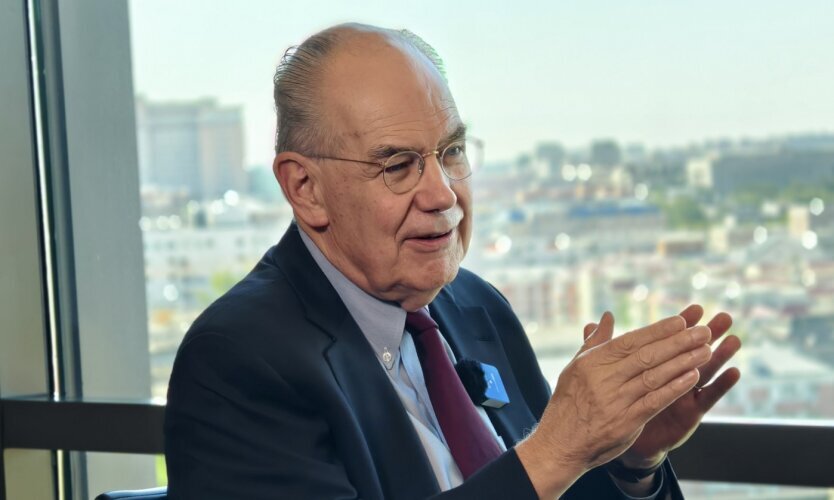

John Mearsheimer is one of the most influential political scientists of our time and, indisputably, the leading voice of structural realism in international relations. For decades, Professor Mearsheimer has challenged comforting illusions about how the world works. He has insisted—often against prevailing wisdom—that great powers are driven not by goodwill or moral aspirations but by fear, competition, and the relentless pursuit of security.

His arguments have been provocative, controversial—and impossible to dismiss. He is the R. Wendell Harrison Distinguished Service Professor at the University of Chicago, where he has taught generations of students to think rigorously and honestly—even when conclusions are uncomfortable—about global politics. His books, including "The Tragedy of Great Power Politics," "The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy," and "The Great Delusion," have become modern classics, translated into numerous languages and debated on every continent.

What distinguishes Professor Mearsheimer is not only the clarity and discipline of his thinking but his intellectual courage. He has consistently spoken truths others preferred not to hear, warning—often long before events—about strategic miscalculations and their consequences. Whether you agree with him or not, it is impossible to seriously engage with international affairs without engaging with his ideas.

Thank you very much, Professor John Mearsheimer. It's a tremendous honor to have you as a guest again. Thank you.

John Mearsheimer: Happy to be here.

The End of Unipolarity

Vuk Jeremić: Let's begin with the big picture. For decades you warned that the "holiday from history" after the Cold War was an illusion and that great power rivalry would return with a vengeance. We're now obviously witnessing a world defined by intense security competition—in Europe, in Asia, in the Middle East. How does the reality of this transition compare to your predictions? In other words, is this the normalcy you expected, or has the shift proven even more dramatic than you anticipated?

John Mearsheimer: I think from about 1992, shortly after the Soviet Union disappeared—and the Cold War had ended by that point—until about 2017, when China and Russia asserted themselves as great powers, we lived in a unipolar world. And by definition, in a unipolar world there can be no security competition because there's only one great power.

But eventually, I think everyone recognized that new great powers would emerge and we would leave unipolarity. My argument is that this happened around 2017, when China and Russia came onto the stage as great powers. So from roughly 2017 to the present, we've transitioned to a multipolar world, and great power rivalry has returned to the agenda.

Almost no one anticipated there would be problems when we left unipolarity and moved to multipolarity. They thought peaceful relations between great powers were permanent. And it didn't matter whether we left unipolarity. I, of course, completely disagreed. I believed China's rise and its transformation into a great power would lead to all sorts of problems in East Asia, and there would be intense security competition between the US and China in that region. Most people thought I was a fool, that this was a ridiculous argument. Unfortunately, I believe I was proven right.

As for Europe, I long argued that attempts to expand NATO eastward, especially to Ukraine, were a recipe for disaster. This would lead to problems with Russia. And of course, these problems began even before Russia became a great power again. The conflict in Ukraine, remember, erupted in 2014, which was still during the unipolar period. In my opinion, only around 2017 did Russia become a great power again. But in any case, the point is that now we have this terrible conflict in Ukraine between the West on one side and Russia on the other. And of course, Ukraine is allied with the West. And again, most people thought we could expand NATO eastward and get away with it, that it wouldn't lead to conflict. And again, I'm sorry to say I was proven right about this too.

Trump 2.0 and the End of Liberal Hegemony

Vuk Jeremić: It appears Washington has fundamentally changed its approach under Donald Trump 2.0. The ambitions to remake the world in America's image seem to have largely evaporated and are now replaced with a much sharper, transactional focus on national interests. To what extent does this new strategy, if it is a strategy, actually align with the realism you've long advocated, rather than being simply a retreat from global leadership, as some other scholars and analysts openly lament?

John Mearsheimer: I know it's fashionable to claim this is a retreat from global leadership and that the US is moving toward an isolationist foreign policy. That's nonsense. That's not what's happening. What's happening is what you described.

During the unipolar moment there was no great power rivalry, as I emphasized earlier. And the US decided instead of engaging in great power rivalry, to remake the world in its own image. To pursue a very liberal foreign policy—what I call liberal hegemony. And as a result, we became bogged down in endless wars. It was a disaster. And consequently, most Americans lost interest in waging these foolish wars.

But more importantly—we transitioned from unipolarity to multipolarity with China's rise and the revival of Russian power under Vladimir Putin. And as a result, finding ourselves in a multipolar world after 2017, the US had to focus on great power rivalry. And of course, they largely abandoned their mission to remake the world in their image, because not only did it fail, but more important questions emerged than spreading liberal democracy. And these more important questions concerned great power rivalry.

So as you rightly noted, Vuk, there has been a shift in American foreign policy, which is largely driven by changes in the structure of the international system—the transition from unipolarity to multipolarity. But it's also because liberal hegemony was a colossal failure. Instead of remaking the world in America's image, we became bogged down in endless wars.

The Russia-China Alliance

Vuk Jeremić: Your well-known thesis is that pushing Russia into China's embrace was a strategic miscalculation of the highest order. Today this alliance appears cemented—Moscow and Beijing are deepening their military and economic cooperation, if not integration. Looking at the structural forces now in play, what, if anything, could pull Moscow away at this stage or drive a wedge between China and Russia? Or must the West accept this bloc as a permanent—or very long-term—feature of the new world order?

John Mearsheimer: Let me start at the most general level. There are three great powers in the system. The US remains the most powerful state, but the US's peer competitor is not Russia but China. China is second, and it's not far behind the US in military power. Russia is the weakest of the three great powers.

In such a world, it makes perfect sense strategically for the US to be allied with Russia and ensure Russia and China are not closely linked, not allies. As a result of the war in Ukraine, we pushed the Russians into the Chinese embrace. And today we have a situation where Russia and China are close allies, which is not in America's strategic interest, as you noted.

I would argue that Trump and his team understand this situation makes no sense. And I believe Trump wants, first, to end the war in Ukraine, and second, to have good relations with Moscow. He wants Russian-American relations to improve so he can pull the Russians away from the Chinese.

By the way, this is a situation similar to what Kissinger and Nixon did in 1972. You remember that, right? In that case, we pulled China away from the Soviet Union. Because it made no strategic sense for us to oppose both China and the Soviet Union as adversaries when there was an opportunity to make China a US ally. And this was, of course, achieved after 1972. And I believe Trump wants to do the same thing—pull Russia away from China now.

Your question is how likely is this to succeed? And my argument is it's highly unlikely in the foreseeable future. In the distant future it might work. But the problem is that it's extremely difficult for Trump to end the war in Ukraine and improve relations with Russia in a meaningful way.

And the reason is that within the West—this is especially true for Europe, but also true for the US—there exists acute Russophobia. Hatred of Russia is entrenched in the ruling classes of Europe and to a significant degree in the US. So it's very difficult for Trump to improve relations with Russia.

Moreover, if you're Russian—do you trust the West? Do you trust the US? I don't think so. And even if you trust Donald Trump, the problem is that Donald Trump isn't forever. This is his second term as president, and after 2028 he will no longer be US president. And his successor may be another Russophobe. So from Russia's perspective, it makes perfect sense to continue having good relations with China.

And of course, from China's perspective, it makes perfect sense to have close relations with Russia. So it's hard to see how we fix this strategic situation that makes no sense for the US.

Europe Without the American Umbrella

Vuk Jeremić: This reality places enormous pressure on Europe. As the US increasingly focuses on the Asia-Pacific region, as well as Latin America, European capitals are actively discussing and promoting strategic autonomy—whatever that means. Given the continent's 80 years of dependence—I'm talking about Western Europe in particular—on the American security umbrella, how realistic, in your view, is the prospect of Europe becoming an independent pole rather than remaining a theater for great power rivalry from outside?

John Mearsheimer: Since the end of the Cold War there's been a very powerful tendency—though you saw signs of it even during the Cold War—to talk about Europe as if it were a single political entity. Almost as if it were a state itself. This is a mistake. Europe consists of a large number of sovereign states.

And the reason one could pretend there existed such a political entity called Europe is that there were two institutions—NATO and the European Union—that brought Europeans together under the American security umbrella. But what's happening now is that the American security umbrella is either disappearing completely or seriously weakening.

And the question to ask yourself is: does this mean Europe will rally closer together? That Europeans will work together more closely than ever because the American security umbrella has disappeared or significantly diminished? My argument is the opposite will happen. European relations will become more conflictual.

The presence of Americans in Europe on a serious scale served as the glue that held Europeans together. Remove the American security umbrella—and there will be conflictual relations between European countries. And it will become impossible to talk about Europe as a single player.

Moreover, one shouldn't underestimate how poisonous relations between Europe on one side and Russia on the other will be for the foreseeable future. The catastrophic consequences of the war in Ukraine are obvious. First and foremost, in terms of what happened to Ukraine. It's a complete catastrophe for Ukraine. But besides that, it has poisoned relations between Russia and Europe for the foreseeable future.

I believe that when the shooting stops and you get a frozen conflict, relations between Europe on one side and Russia on the other will be poisonous. And as a result, you'll get splits in Europe because of this situation with Russia. There will be countries in Europe that want to have friendlier relations with the Russians. And there will be countries in Europe that want to have even more hostile relations with the Russians. And of course, the Russians will have very powerful incentives to exploit these disagreements in Europe and sow discord.

So in the future, I would argue, Europe will look less like a single political entity than in the past—first, because the American security umbrella is either disappearing or will be significantly reduced, and second, because of the poisonous relations between Europe and Russia that will likely be established after the cessation of hostilities in Ukraine.

Middle Powers: Hedging Between Giants

Vuk Jeremić: Let's step away from great powers for a moment. We're witnessing assertive diplomacy from rising middle powers—such as Brazil, India, Saudi Arabia, or Turkey. These countries seem intent on hedging rather than joining one bloc. How much real agency do these states possess? In other words, can they maintain this independence or hedging position long-term, or will the gravitational pull of the US and especially China ultimately force them to choose sides?

John Mearsheimer: I think there's no doubt that most states in the international system prefer to hedge and not enter into direct alliance with either China or the US in this security competition that's heating up between the two great powers. This is especially noticeable in East Asia, where numerous countries have first-order economic relations with China, and they want to maintain these good economic relations, and therefore are afraid to get too close to the US. But at the same time, they understand that if they're threatened by China, they'll have no choice but to ally with the US.

They want to have their cake and eat it too—hedge, have good relations as much as possible with both China and the US.

The problem for any particular country is that if China becomes a serious threat to your survival, or the US becomes a serious threat to your survival, you really have no choice but to side with the other country, because security always trumps prosperity. Which means economic relations are always subordinate to security relations when your survival is at stake.

Therefore you see countries like Japan and South Korea, the Philippines, Australia—all have drawn very close to the US. But in places like Southeast Asia, you see a lot of hedging.

Some of the countries you mentioned are very interesting cases. Let's start with Brazil. Brazil is in the Western Hemisphere. The US has a policy called the Monroe Doctrine. And the Monroe Doctrine says Brazil can in no way form an alliance with China. And I think the Brazilians understand perfectly well they can have economic relations with China, but they have no choice but to be friendly to the US, not to ally with China. This is true for every country in the Western Hemisphere. And if anyone has doubts, remember what happened to Cuba when it allied with the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

India is the most interesting case of all, because over roughly the last 25 years, US-Indian relations have significantly improved. And because India has a border conflict with China, it was moving ever closer to the US. But as a result of the war in Ukraine, President Trump played hardball with India over its trade with Russia. And he imposed 50 percent tariffs on India. And I would argue President Trump poisoned relations with India.

The result is India is seriously hedging, and if anything, leaning toward China rather than the US—in the opposite direction from where it was moving in recent years. India actually possesses significant agency, and it has responded to American policy in ways that are not in American national interests—and this is largely the result of President Trump's foolish policy stemming from the war in Ukraine.

As for countries like Turkey and Saudi Arabia, I think they will clearly lean toward the US in the future, largely because neither China nor Russia has that much influence in the Middle East. The US is the great power that truly dominates the Middle East at the moment. And therefore these two countries—Saudi Arabia and Turkey—when push comes to shove, ally with the US.

However, I would argue that as China becomes more powerful and develops a blue-water navy and the ability to project power into the Persian Gulf, what countries like Saudi Arabia and Iran do in the future remains an open question. It may happen that Saudi Arabia moves away from the US and develops much closer strategic relations with China. Time will tell. But remember that the balance of power between China and the US is shifting. And China is becoming increasingly powerful and developing significant power projection capability, which will affect how countries around the world respond to China or the US.

International Institutions: The End of Global Order?

Vuk Jeremić: Let's move to the international organizations we still have, though they're collapsing or seem to be seriously struggling for survival against this backdrop of renewed great power competition. The paralysis of the UN Security Council comes to mind, the fragmentation of the WTO. This seems to suggest the institutional architecture from 1945 is crumbling.

You've long argued that institutions merely reflect the balance of power in the world. So if these forums are indeed hopelessly deadlocked, as some say, what mechanisms remain for ensuring basic diplomacy between the great powers, as well as for the rest of the world?

John Mearsheimer: Let me make two sets of remarks, Vuk. First, during the unipolar moment there was one great power. And that one great power was the dominant force in the international order, right? In those international institutions that constitute the international order. But we've moved from unipolarity to multipolarity. And now you have three great powers. And as you noted, this will fundamentally change the politics within these international institutions. The US is no longer the only great power. They don't run the rules-based order the way they did during unipolarity. They have to worry about competing with China and Russia in the context of these international institutions.

And by the way, this is no different from the situation that existed during the Cold War, when the Soviet Union and the US were great powers and rivaled each other, competed within international institutions like the UN, right? And all that changed again with the arrival of unipolarity. But now we've left unipolarity behind and are in multipolarity. So these international institutions that exist—and they still exist, the US hasn't gone away, the WTO hasn't gone away, the Non-Proliferation Treaty hasn't gone away—but the fact is that over time it will become increasingly difficult, and already is difficult, to get much cooperation between the three great powers in these international institutions. So essentially you're right.

My second remark: you need to understand that China and the US are creating their own limited orders. These are smaller orders, but powerful orders designed to wage security competition. And if you recall the Cold War, you need to remember that within the Soviet world, within what was then called the communist world, the Soviets built their own order. It included institutions like COMECON (Council for Mutual Economic Assistance), the Warsaw Pact, and so on. And within the West, the US built its own order. These weren't international orders—they were limited orders. They were designed to wage security competition.

And what you see now—take China as an example—it's building its own limited order. Think about the Belt and Road Initiative. Think about BRICS. Think about the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. Think about the AIIB (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank). All these are institutions within the Chinese order that don't include the US. And of course, the US has its own limited order.

So it's very important to understand: the international order—that is, institutions that include all great powers—is weakening. However, we're seeing the development of limited orders—one led by China, another led by the US—designed to wage security competition between these two great powers.

Economic Interdependence: The Illusion of Peace

Vuk Jeremić: Let's stay with this breakdown of governance that's noticeable now in the global economy and markets, where security considerations outweigh economic efficiency—as you've always argued. This is obvious in the decoupling of high-tech supply chains. And high technology is a major driver of global growth and domestic economies worldwide, this is extremely important. Does this confirm the argument that high levels of economic interdependence are actually dangerous rather than stabilizing? And how much economic pain, in your view, are great powers willing to endure to secure their supply chains?

John Mearsheimer: A couple of remarks. First, many people believe economic interdependence leads to peace. And the argument is that economic interdependence promotes prosperity. And if countries become economically prosperous, why would they start a war and ruin that prosperity? It makes no sense at all.

So in past years, when I argued the US and China would likely end up in dangerous security competition, many of my interlocutors objected that this was wrong because of all the economic interdependence between China and the US. There would never be serious security competition, let alone war. I usually reminded people that there was enormous economic interdependence in Europe before World War I, but World War I still happened. So don't count on economic interdependence to bring peace.

My conclusion on the question of war and peace: I don't think economic interdependence causes war, and I don't think it leads to peace. It doesn't matter much. It may matter at the margins in individual cases, but overall it's not particularly important.

Where economic interdependence matters today, especially for the US, is that the US depends on China for certain materials. And this gives China great leverage over the US. I'm talking mainly about rare earth elements and magnets—rare earth magnets.

As you remember, when President Trump took office in January 2025, he almost immediately decided to play hardball with China. He talked about imposing massive tariffs on China and making China dance to his tune. This didn't last long, because the Chinese reminded President Trump that the American economy heavily depends on rare earth materials and rare earth magnets. And the Chinese made it unambiguously clear to President Trump that they would stop supplying these rare earth metals to the US if the US played hardball. And as a result, President Trump backed down. He's no longer playing hardball with the Chinese.

All because the Chinese have significant leverage over us—we depend on China. This is one result of economic interdependence, a result of supply chains on which the US depends and in which China plays a key role. We're trying to fix this situation. But it's very difficult to do.

So you see that in the current situation, it's not that economic interdependence caused war or promoted peace. But economic interdependence has put the US in a disadvantageous strategic position. The US doesn't want to be in a situation where it depends on China for rare earth metals or rare earth magnets. But that's exactly where we are. So economic interdependence has real limits, as the US is now discovering.

Flashpoints: From Taiwan to the Black Sea

Vuk Jeremić: History shows multipolar systems are prone to miscalculation. You mentioned Europe and World War I—because of the very complexity of the board. So surveying the board, the global board today, where do you see the greatest risk of accidental hot war erupting? Is Taiwan the obvious main flashpoint, as many say? Or are we missing other dangerous fault lines?

John Mearsheimer: Let's talk first about East Asia and Taiwan, then move to Europe, where I think there's enormous potential for problems in the future.

First, regarding East Asia, there are three main flashpoints between China and the US in this region. The first, which you mentioned, is Taiwan, which is obviously very dangerous. The Chinese are deeply committed to bringing Taiwan back. They believe Taiwan is sacred territory and belongs to China. At the same time, there's no doubt that strategically the US, Japan, and other East Asian countries don't want China to take Taiwan. The US and Japan are deeply committed to Taiwan remaining independent. So you see Taiwan is a dangerous flashpoint, certainly.

But there are two other flashpoints that concern me greatly. One is the South China Sea. The Chinese believe the South China Sea essentially belongs to them. It's not international waters as the US and its allies say—it's Chinese waters. So there's real potential for conflict over who controls the South China Sea.

And then there's the East China Sea, where tiny islands that the Japanese call Senkaku and the Chinese call Diaoyu are disputed territory. Japan currently occupies these islands and believes they belong to it. The Chinese completely disagree—they're convinced these are Chinese islands. And moreover, there's a dispute over who controls the East China Sea. The Chinese want to dominate the East China Sea, and the Japanese don't want that.

So again, you have three main flashpoints in East Asia: the South China Sea, the East China Sea—which of course includes the Senkaku or Diaoyu islands—and then, of course, Taiwan.

But let's move to Europe. First, even if you resolve or stop hostilities in Ukraine, you'll get a frozen conflict in Ukraine. And there's always the danger this frozen conflict will turn into hot war again. You'll go from cold war to hot war. So Ukraine itself will remain a dangerous flashpoint in Europe.

But I would argue there are six more dangerous flashpoints in Europe that are closely connected to competition between Russia on one side and Europe and the US on the other. And these six potential flashpoints in Europe are: the Arctic—where remember that seven of the eight countries physically located in the Arctic are NATO countries. The Russians are outnumbered seven to one. And there are all sorts of potential problems that could lead to conflict in the Arctic.

Then the Baltic Sea. Then Kaliningrad. Then Belarus. Then Moldova. And then the Black Sea. I could tell you a story, as you could tell me a story, about how you could get a war between Russia on one side and one or more European countries on the other in each of these cases.

So Europe will remain a very dangerous place in terms of the possibility of war for the foreseeable future, just as East Asia will remain a very dangerous place.

Vuk Jeremić: I breathed a sigh of relief when you said six. I thought: the Balkans will surely be one of these six. But your list stopped without including the Balkans—and yet in the past you've proven a true prophet regarding what can happen in the world. But let's move on.

Can a Divided America Act Rationally?

Vuk Jeremić: Realism—you're its chief bard and leading scholar. It typically assumes, if I'm not mistaken, that states act rationally to survive, regardless of their domestic politics. And the exceptionally deep polarization in the US now is undeniable. So how does this domestic dysfunction affect America's ability to act as a rational balancer in the world? And can a divided hegemon, still the world's strongest country as you said, effectively maintain credibility in its security commitments abroad?

John Mearsheimer: Let me start by saying I do assume in my theory, as do almost all realists, that states act rationally. But states sometimes don't act rationally. My argument is they usually, or typically, act rationally. But there are cases when states don't act rationally. And remember that theories are simplifications of reality. And no theory can explain every case. So a good realist theory will explain most cases, but there will be cases when states act non-rationally or irrationally.

And the question you're asking—a very important question—is whether the conflict within the US between the red side of the political spectrum and the blue side of the political spectrum will cause non-strategic or irrational behavior by the US.

And I think the answer is no. And there are two reasons. First, there's not a big difference between the two sides regarding foreign policy, especially when it comes to great power politics. Many people argue Republicans and Democrats are essentially a "uni-party" when it comes to foreign policy. They basically think and act very similarly.

So this political division in the US, which is clearly poisonous—I don't want to downplay it—and there's no doubt the US has problems on the domestic front. So I'm not denying that. But in terms of foreign policy, I don't think you see this big division within the US reflected in our foreign policy. So I don't think domestic politics will cause us to act irrationally for that reason.

But the second point—as a structural realist I believe structure largely determines the behavior of states. And the US faces a serious threat from China. And it has a deeply rooted interest in containing China. And I think this point is recognized by people on the left and right, or people on the blue side of the equation and people on the red side of the political equation. Containing China is seen as a strategic imperative by almost everyone in the foreign policy elite within the US.

This doesn't mean denying that people will have different views on exactly how to contain China. That situation will always exist. This was true during the Soviet Union. There was broad agreement in the US that we needed to contain the Soviet Union during the Cold War. But how to do it wasn't always a question people agreed on. And I think this will be true regarding China.

But if you look at US foreign policy toward China in the future, it's unlikely the US will act irrationally or strategically foolishly. This is always a possibility. Again, I want to emphasize no theory can predict every case, and sometimes states act in ways that contradict what basic theory says.

Regarding US relations with China, it's quite likely we'll behave strategically smart and rationally.

Trump and Ukraine: Attempting to Correct Irrationality

Vuk Jeremić: But then Donald Trump and his attitude toward the war in Ukraine—is this just a deviation? This was quite a dramatic change from the Joe Biden government to this US government in terms of how they approached this crucial conflict in Ukraine. So I'm a bit confused. Are you trying to say that after Trump, everything will return to the uni-party consensus on foreign policy? That Trump won't have a lasting impact on some strategic shifts in how the US deals with the world?

John Mearsheimer: Look, I think current US policy toward Ukraine is not rational. That we're pushing the Russians into the Chinese embrace makes no strategic sense. There's no doubt about that.

And what Trump is trying to do is fix this situation. He's trying to act strategically smart, rationally. The problem is that because of Russophobia in the West, it's very difficult for him to achieve his goal. But he's acting strategically smart.

But the US, in a very important sense, is stuck in a rut. Stuck in a policy that makes no strategic sense. And this policy, by the way, was initiated during the unipolar moment. What the US was trying to do during the unipolar moment was spread liberal democracy and liberal institutions into Eastern Europe, make Eastern and Western Europe a single entity. This idea was at the heart of our Ukraine policy—and was launched during the unipolar moment.

But then we moved from unipolarity to multipolarity, and you had US-China competition. But the US got stuck in this war in Ukraine that made no strategic sense. It was irrational at that point to push the Russians into the Chinese embrace. We were no longer in unipolarity—we were in multipolarity. And the Biden administration acted, I think, irrationally, non-strategically, by escalating tensions with the Russians and then essentially doing almost nothing to prevent the war in Ukraine from starting in 2022. That was strategically foolish.

And again, I want to say Trump is trying to fix this situation. Trump is acting rationally, in my view. Whether he can solve this problem is another question.

Vuk Jeremić: Professor John Mearsheimer, one of the world's most influential strategic thinkers, uniquely able to explain complex processes and structural forces in world politics. A tremendous honor to speak with you again, sir. Thank you very much for this interview.

John Mearsheimer: Thank you very much for your kind words and thank you for inviting me to the program. I really enjoyed it.