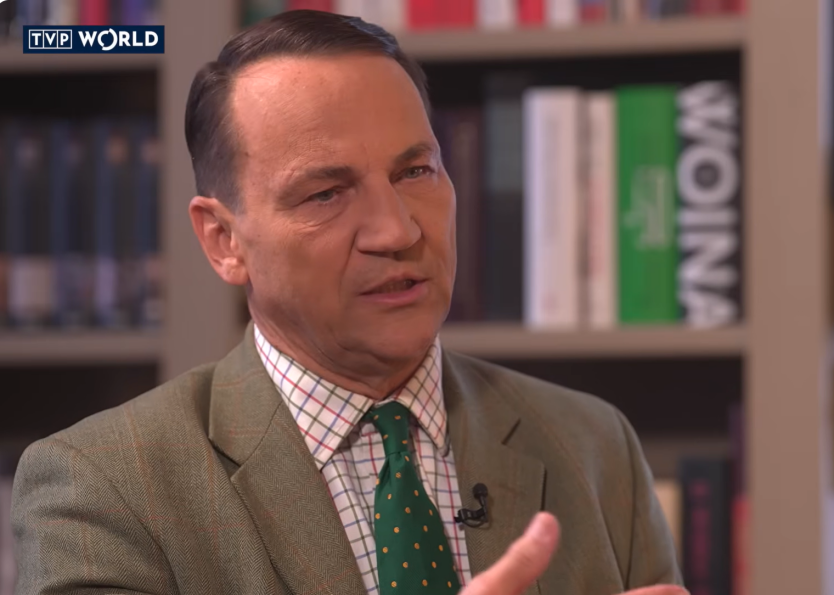

Radosław Sikorski spent years warning the West about Putin – and was proven right. In an interview with Between the Lines, Poland's foreign minister explains why Europe can no longer rely on the United States, how $90 billion changes the Kremlin's calculations, and why a "frozen conflict" in Ukraine is dangerous. A frank conversation about the new reality of European security – from a man who saw its approach long before others.

Urszula Gacek: Welcome to Between the Lines. I'm Urszula Gacek, and my guest today is Poland's Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski. Minister, thank you so much for joining me today, and thank you for hosting us in your home.

Radosław Sikorski: My pleasure.

Urszula Gacek: It's a pleasure to be here. Minister, many years ago you warned Western leaders about Vladimir Putin. Today, do you feel vindicated, or do you experience a deeper disappointment that it took a war for you to truly be heard?

Radosław Sikorski: I would have preferred not to be vindicated in this way. Poland would be a more secure country if there were Western democratic states on both sides of our border. And that's why, as the West and as Poland, we bent over backwards trying to help Russia choose the path of development and democracy. Unfortunately, Vladimir Putin couldn't stay on that course, because I think at the very beginning he tried. And then, when he started invading neighbors, only one possible response remained, which is to try to contain him and resist him.

Urszula Gacek: We were indeed doing this back in 2008, 2009 with the then Swedish Foreign Minister Carl Bildt – you had a fantastic Eastern Partnership initiative. It actually built on Poland's long-standing tradition, developed in the mid-20th century by Giedroyc in Paris in exile, which essentially stated that Poland's security depends on having safe and democratic neighbors. We focused then on Belarus, on Ukraine, on Georgia, Armenia, Moldova. Some of them fell by the wayside. What happened to such a project? Is this project relevant today, if we look at Georgia, for example?

Radosław Sikorski: Of course there's much to discuss here. First of all, remember that Jerzy Giedroyc was a man of the Second Polish Republic. And so it was quite revolutionary for him to assert after the war in Paris and in émigré circles that Poland should in the future recognize the borders imposed on Central Europe by Stalin, essentially, and then try to establish normal relations with the peoples with whom we previously shared statehood. Ukrainians, Belarusians, Lithuanians and so on. And remember that this Promethean idea of helping our Eastern neighbors become democracies was also accompanied by a desire, perhaps a dream, of more normalized relations with Russia. There was a time, I would recommend you read George W. Bush's speech to Poland at Warsaw University in 2001, three months before 9/11, when the United States defined success as "Europe whole and free," and by that they meant a democratic Ukraine and Belarus.

Much has happened since then. The Eastern Partnership was a Polish idea, supported by Sweden, which Prime Minister Tusk convinced the entire EU to adopt. A program of soft encouragement for countries of the former Soviet Union to adopt our standards. Backed by real money. 1.5 billion euros a year. To have more civilized border crossings. To have biometric passports. To have cross-border cultural and environmental initiatives. For civil society to unite.

Urszula Gacek: That was an important component, the democracy support fund, yes.

Radosław Sikorski: Of course. And it still exists. But as you say, some countries used the Eastern Partnership to become closer to the EU and become candidates. Ukraine and Moldova. Georgia was on track to become a candidate and unfortunately veered off course. And some countries don't even try, don't even pretend to be on a convergence course.

Urszula Gacek: I think wasn't Azerbaijan also in the original composition?

Radosław Sikorski: Of course, but Belarus unfortunately as well. But interesting things are happening in Central Asia. That's why, on our initiative, TVP World is developing new language services in the languages of the Caucasus and Central Asia, and good luck to them.

Urszula Gacek: Minister, let's return to Russia and, of course, what's happening with Ukraine. There are apparently some positive notes coming from the recent negotiations at Mar-a-Lago. They were called "constructive." Anyone who's ever been a diplomat knows that word conceals many facets. But from Russia's side, there are still no meaningful concessions. Do you see anything that will make Russia sit at the negotiating table?

Radosław Sikorski: What will bring Russia to the negotiating table is further degradation of the Russian economy, so that Putin understands he cannot achieve his military goals by continuing the war. And he's not there yet. He still dreams of subjugating all of Ukraine, which is unachievable. If you look at the map of his military conquests over the past year, for which he paid with tens of thousands, perhaps more than a hundred thousand deaths of his soldiers, at this rate it will take him decades to conquer Ukraine. But this is the problem with dictators – when you're in power for 20 years, very few people will tell you the truth. And people only bring good news. That's why I believe the war will end based on how much pressure we exert on Putin, on the aggressor, not on the victim of aggression.

Urszula Gacek: Exactly. But we're approaching the fourth anniversary of the full-scale invasion, and what will this be, the 20th round of EU sanctions? Every few months we have new sanctions. Is this a natural escalation, when we started softer and now we're acting tougher, or does it mainly show us that these sanctions are being circumvented, that they're unsuccessful?

Radosław Sikorski: Both yes and no. Because some sanctions are an escalation. So for example, the United States imposed sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil, fine. And our European sanctions also cover new organizations. But some of them need constant updating. Let me give an example. We have sanctions against the so-called "shadow fleet," tankers that help export Russian oil. You need to constantly update the list, the names of tankers, the names of captains and crews. So even if we weren't strengthening sanctions, new rounds would still be needed.

Urszula Gacek: A difficult question. Poland, despite its frontline position and the scale of support we've provided to Ukraine in virtually all aspects, especially militarily, economically, and in Polish society, is not currently at the negotiating table with the US, French, Germans and British. And some criticize this and view it as a failure of Polish diplomacy. How would you respond to such criticism?

Radosław Sikorski: Well actually, Prime Minister Tusk was just in Berlin where there was a meeting. And our national security advisors, as we speak, are in Kyiv, all the European ones plus high-level officials from the US. There are different formats. There are European formats, in some of them Europeans participate, in others they don't. Yes, I mean, Poland has some arguments. We're not only the only NATO and EU member that borders both countries, and we're an indispensable logistics hub for supporting Ukraine. But on the other hand, as you know, the President of Poland said that under no circumstances will he allow any Polish military presence in Ukraine. While the coalition of the willing is discussing precisely that. So there are these arguments for and against including us in various forums.

Urszula Gacek: But I also suspect that public opinion doesn't see this as often. There are some negotiations happening, for example, about prisoner exchanges. Things that perhaps aren't on the radar, but Poland is present at these negotiations, would you say?

Radosław Sikorski: Actually they're happening between Russians and Ukrainians. And in places like the United Arab Emirates. During such a war there are always different communication channels. There are channels through Turkey. China is involved. The UN. The UAE, which we've already mentioned. Poland's interests are in Ukraine being supported in the fight. That's why we contributed to the purchase of American weapons for Ukraine. We've transferred, we're now, I've lost count, I think at the 48th transfer of equipment to Ukraine. But Ukraine reciprocates by relocating part of its drone and missile production to Poland. We're using the EU's "Safe" mechanism, under which 44 billion euros will be spent on strengthening the defense industry. Some projects will be implemented jointly with other European partners, and also some with Ukraine. Much is happening. What's really important is that we've found a way to assure Ukraine that its state functions and its defense budget will be supported by the EU with $90 billion over the next two years. This, I think, changes Putin's calculations. Because he perhaps hoped, as he's done from the very beginning, that democracies are pathetic, that democracies lack endurance. Now he must be prepared to fight for another two years. And it's unclear whether his army and his economy can bear this burden.

Urszula Gacek: So in a sense the support will allow Ukraine to become self-sufficient in many respects. With the support of European partners, European financing, which is key. I think Ukraine has experience with agreements that weren't upheld, going back to when the Soviet Union...

Radosław Sikorski: Well, this is one of my arguments in conversations with Western colleagues. You know, the list of agreements where Western Europeans make decisions over the heads of Central and Eastern Europe is long and very sad. And we know what those agreements are. The last ones, of course, were Minsk-1 and Minsk-2, and we don't need Minsk-3. But yes, Ukraine needed money to fully produce in its own factories, in the unoccupied parts of Ukraine, its own equipment and ammunition. And we have much to learn from Ukraine, because they have experience conducting modern interstate warfare. We've been preparing our army for 20 years to conduct expeditionary wars. And now we have to face reality.

Urszula Gacek: Let's go across the Atlantic. The last National Security Strategy that came out of the White House at the end of last year. I think there were, perhaps, some sensational reports that this is an abandonment of Europe, that this is American interference in how we manage our continent. Is everything so bad? How would you...

Radosław Sikorski: I actually appreciate the fact that the US released a document that is hyperrealistic, that is more, one could say, honest about America's actual capabilities. You know, they've been telling us for a long time that they no longer have the capability to conduct two major wars simultaneously. And now they've dotted the i's. There are also some provocative ideological statements there that awakened Europe. What we'll need to track is the National Defense Strategy, where they'll say how many troops they want in Europe. And that's in a sense more important, certainly for us. And all the signs we're getting in Poland say that the US is not only maintaining its position here, but is actually preparing to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in American facilities in Poland.

Urszula Gacek: At the moment, that's actually good business.

Radosław Sikorski: Well, the US has a very favorable Status of Forces Agreement. We contribute about $15,000 per soldier per year. Which, you know, is our argument, it's true. It's cheaper for the US to maintain an American soldier and train him or her in Poland than in the US. It's mutually beneficial. So let's wait for that, and then for the force posture review. I don't believe the US will leave Europe altogether. It will be a different type of alliance. The US is signaling to us: you must take on a greater share of the burden of conventional defense in Europe. And we'll support you from over the horizon with a nuclear umbrella, targeting and intelligence, and auxiliary means like air-to-air refueling. And this could be a new type of alliance that might be more sustainable in the long term. You know, let's give credit where it's due. President Trump was right at the very beginning of his first term when he said that Europe had been consuming "peace dividends" for too long. And we heard him and have doubled our spending since then.

Urszula Gacek: So this is the new normal? This is the new normal in transatlantic relations, because we're looking even now, perhaps at midterm elections that will happen at the end of this year. It's possible that the House of Representatives will go back to the Democrats. Some experts say that perhaps even the Senate could go to the Democrats. Unlikely, but possible. Can you imagine if, for example, the House goes to the other side, and Trump doesn't have Congress behind him, will you see a change in strategy on this front? Or is this actually a new normal that will extend beyond the Trump administration?

Radosław Sikorski: My argument is different. Regardless of who wins this year or in the presidential election in two years, we need to do what we need to do, namely rebuild our defense industry, rebuild our armed forces. Poland is acting proactively, but I'm talking about most of Europe. To be able to deter Putin regardless of what the United States does. Because intentions are one thing, and the US has warned us. But capabilities are another. If the US gets involved in a war in Asia, which we can't rule out, they may not be able to help us. And so we have time until the end of the decade to build armed forces that Putin won't want to challenge. And this shouldn't be beyond our capabilities. You know, our economy is nine to ten times larger, I'm talking about the EU, than Russia's. And you know, we successfully fought Russia even before the United States existed. So we should be capable of doing it today.

Urszula Gacek: You mentioned Asia. Minister, I'd like to refer to a statement you made in Strasbourg as a member of the European Parliament in 2023 about China. "We have two red lines: don't arm Russia and don't attack Taiwan." Have they crossed the first line and are they flirting with the second?

Radosław Sikorski: They haven't crossed the first line. I haven't changed my opinion. I have frank discussions with my Chinese counterpart. And during one of them he told me, quite wittily, I thought, that if they, China, were helping Russia in the war as much as we Europeans say, the war would already be over. China supplies Russia with all kinds of goods, including dual-use goods, but not actual lethal weapons. And as for Taiwan – this is China's declared national security goal. Poland has a "One China" doctrine. We say there is one China, but we don't prejudge...

Urszula Gacek: That is, rather like Nixon and Kissinger then, I think, when the famous diplomatic phrase "constructive ambiguity" was formulated, when you have a document that both Taiwan and China were satisfied with after that discussion, when Nixon went to China with Kissinger. Are you worried that when we have some agreement that, hopefully, will end the war in Ukraine, do you think it will be solid enough? Do you think there will be a temptation to make it ambiguous in some sense, so that everyone leaves the negotiating table happy, but we end up with some frozen conflict that could rumble on for years or even decades?

Radosław Sikorski: I really am worried about this, because we need the war to end with Ukraine that is not only free to integrate with the European Union, but must also have borders that can be defended. Otherwise it's a recipe for another war in a few years.

Urszula Gacek: Essentially, just postponing the problem.

Radosław Sikorski: You know, the Franco-Prussian War ended with Germany controlling lands on the western bank of the Rhine. This had to lead to another war, and it did. And so we don't want to repeat that mistake. But we'll only get a just solution when Russian elites come to the conclusion that the initial invasion was a mistake and that the goal of restoring the Russian Empire is unachievable.

Urszula Gacek: So there's no face-saving option for Putin?

Radosław Sikorski: Well, Putin probably thinks that by demanding only Donbas, he's making a concession. But of course this... this means the aggressor will be rewarded. And the Ukrainians, I think, now that they have these $90 billion, are determined to continue fighting, to resist.

Urszula Gacek: May I ask a personal question, perhaps in closing? Oxford University educated many world leaders. You arrived there as a...

Radosław Sikorski: And some very good journalists.

Urszula Gacek: A very young 19-year-old in the early 80s. Did you imagine that one day you'd join their ranks?

Radosław Sikorski: What I didn't imagine was that there would be a world where Poland would be a very successful EU member with a very successful economy, and Britain wouldn't be a member. I recall my time at Oxford with great sentiment. And I think Polish-British relations are excellent.

Urszula Gacek: Minister, thank you very much. It was a pleasure to be here, in your home. And we look forward to your next UN speech, which I believe went viral.

Radosław Sikorski: Well, next month there will be my speech in the Polish parliament, and it will be one of... it's my 10th, and it will be the most difficult.

Urszula Gacek: So stay tuned. Please do. Thank you very much, Minister.

Radosław Sikorski: Thank you.